News

Prabowo regime rewriting national “his-story”

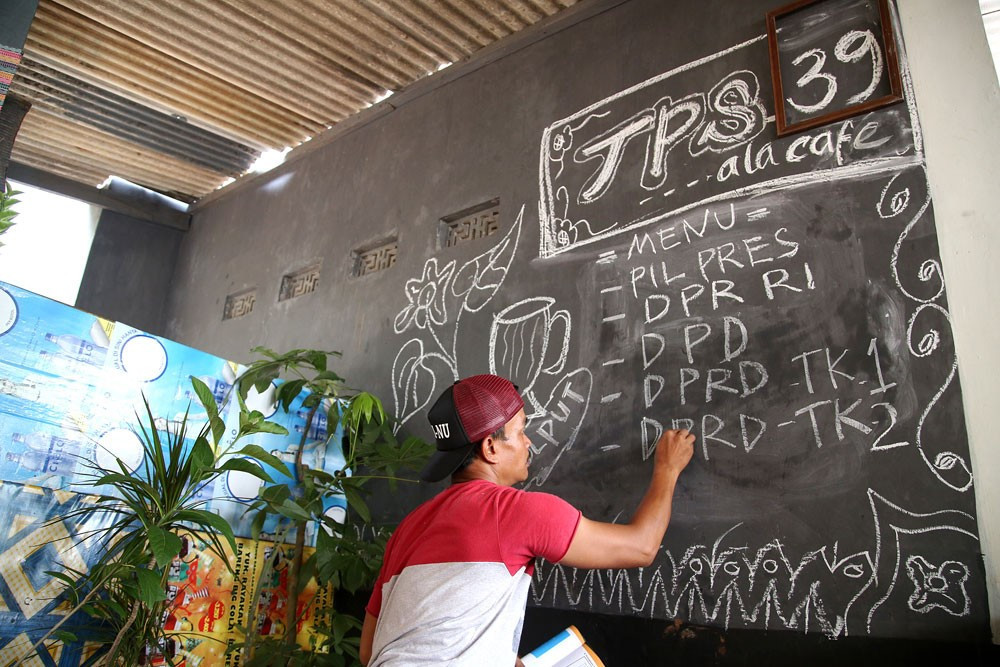

Tenggara Strategics May 19, 2025 Nadi Kusnadi, a resident of Leuwinanggung, Depok, in West Java, decorates polling station 39 to resemble a cafe, a day before the simultaneous presidential and legislative elections. (The Jakarta Post/P.J.Leo) (The Jakarta Post/P.J.Leo)

Nadi Kusnadi, a resident of Leuwinanggung, Depok, in West Java, decorates polling station 39 to resemble a cafe, a day before the simultaneous presidential and legislative elections. (The Jakarta Post/P.J.Leo) (The Jakarta Post/P.J.Leo)

When the government completes rewriting the official national history, scheduled for August, do not expect too much change on topics that are too politically sensitive to be written in a more honest and objective way. The more recent history will likely be much trickier to write, and to read, for that matter, as many of the (bad) actors are still alive.

Critics see this more as a political project, some even suggesting that it is aimed at giving legitimacy to the current regime of President Prabowo Subianto . The timing is clearly political with Cultural Minister Fadli Zon promising to complete the revision on time for the Aug. 17 Independence Day, as an 80th anniversary gift from the government.

Launched in January, the team of more than 100 historians and archaeologists recruited for the project has seven months to rewrite the entire national history, going all the way back to prehistoric time and all the way through 2024. That is too short a period for such an ambitious undertaking.

Fadli revealed some of the changes that will come with the revision, but also some that will not be altered despite controversies surrounding them.

One major change in the official history, one that is already widely discussed and accepted by many, is that Indonesia was never colonized by the Netherlands for as long as three-and-a-half centuries. The first Dutch traders arrived before the turn of the 17th century in search of spice, but they conquered what is now Indonesia over a long stretch of time. Sumatra only formally became part of the Dutch East Indies towards the end of the 19th century.

That perspective worked its way into national consciousness in the wake of Indonesia’s independence in 1945, and it had worked well to galvanize the revolutionary spirit important at the time. Seen by some as a consolation prize for the former colonial masters, a popular line found in many school history textbooks in the mid-20th century was that “three-and-a-half years of Japanese occupation was worse than three-and-a-half centuries of Dutch colonialism,” which is another myth.

Fadli said rather than talking about Dutch colonialism, the new official history would highlight armed resistance against Dutch forces trying to impose their rule in the region.

The active collaboration of the rulers of the dozens of sultanates who played a key role in enabling Dutch traders and forces to extract so much profit that they turned the Netherlands into one of the wealthiest nations on earth in the 18th and 19th centuries would be spared by historians. Closer scrutiny of their role could explain why the republic today is still grappling with corruption.

One official history that will not be altered surrounds events in 1965 that saw the Army crushing the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). The official version, written by military historians, had the PKI plotting a coup against president Sukarno but was foiled by the Army commanded by Gen. Soeharto. The event paved the way for his rise to power, replacing Sukarno the following year.

One version that challenged the official narrative, written by scholars at Cornell University, suggest that this was an internal Army affair that began with the kidnapping and killing of six Army generals by younger officers. The PKI, outlawed since then, was made the scapegoat.

There are still many unanswered questions surrounding this event. The ensuing mass slaughter of communists and their sympathizers by the Army and auxiliary organizations, with a death toll estimated by some scholars of over 1 million, is not acknowledged in the official history. What is sure is that Soeharto ruled the country with an iron fist for the next 33 years.

Fadli made it clear that the history surrounding 1965 and the aftermath will not be reviewed.

It is not clear how much freedom historians in the project have in revisiting the historical narrative of many of the bloody rebellions that occurred in Indonesia since its independence, from the Indonesian military campaign to wrestle Papua from Dutch hands in the 1960s to Indonesia’s annexation and subsequent military occupation of East Timor, now renamed Timor Leste since its independence in 1999. These events are still shrouded in controversy, with the official history tending to glorify the military’s role in the nation-building process.

Project leader Susanto Zuhdi, a history professor from the University of Indonesia, said this month that the team has completed around 70 percent of the writing. The national history would be contained in 10 volumes.

President Prabowo is a history buff, according to close friends. In one recent Cabinet meeting he related that the Netherlands was behind some of the rebellions in the early years of Indonesia’s independence, including one launched by PKI in 1948 and another by the group known as DI/TII that sought to set up an Islamic state.

Historians trying to piece together the history of Indonesia face a major challenge due to the lack of authentic documents and artifacts, and most of these are found and preserved in the Netherlands.

Not much is known or written about the brutality of Dutch colonialism, with most Dutch literature being self-exculpating in its positive portrayal of their colonialism in this region.

Some historical novels have helped to shed some light on the real condition during the colonial time, including Max Havelaar, published in 1860 and written by a Dutch author under the pen name Multatuli, who gave a shocking account of the abuses of Dutch rulers in the East Indies.

Indonesia’s renowned author Pramoedya Ananta Toer came up with a series of novels about life under Dutch colonialism called the Buru Quartet. Dying in 2006, Pramoedya was forced to do hard labor at the Buru Island penal colony with tens of thousands of others who were rounded up by the Army in 1960s suspected of being communists. The Buru Quartet was developed out of an oral narrative which he shared with his fellow political prisoners. His books were banned under Soeharto almost immediately after their release because his stories described class struggle.

Works of fiction can sometimes give a better picture of reality than official historical narratives influenced by political interests and agendas.

What we've heard

According to a source familiar with the move, Fadli has involved more than 100 experts to write, revise and rewrite the history that has been taught in schools. “This will be the official reference for teaching history,” the source said.