News

Corruption overshadows discourse on political party financing

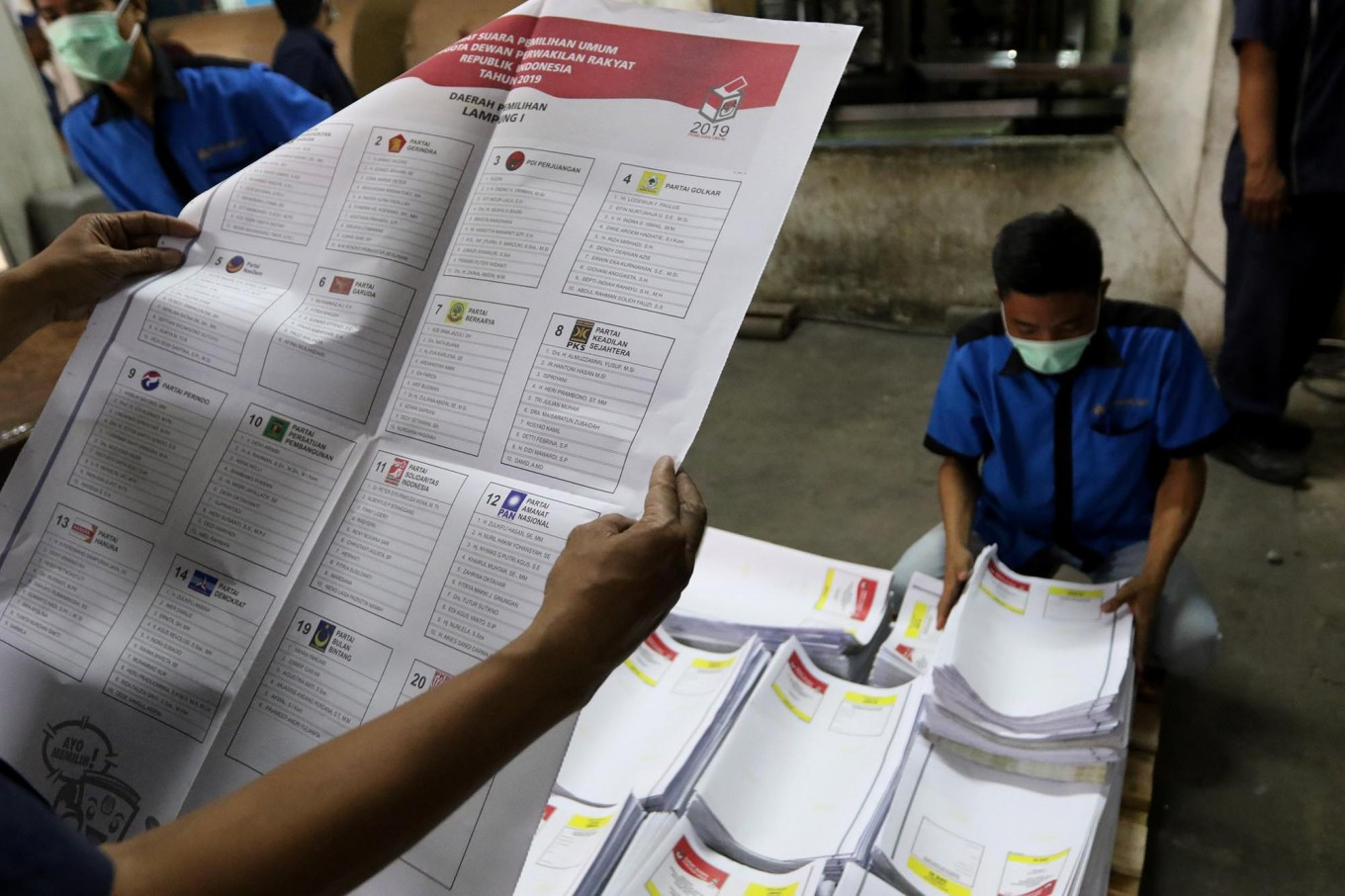

Tenggara Strategics June 2, 2025 Staffs are folding the ballot papers. (JP/Dhoni Setiawan)

Staffs are folding the ballot papers. (JP/Dhoni Setiawan)

Every five years, Indonesia holds a multi-party general election typically participated in by around 20 political parties. But every time the nation launches a discourse on how best to finance these parties, someone in the room will quickly shout “corruption”, a reflection of the distrust the public has toward them.

Parties have themselves to blame in part because of the endless corruption cases involving their top leaders that have gone to the court of justice. Yet they have a legitimate reason to want to raise money since almost all of them are run on shoestring budgets. They have to find creative ways to raise money to run the parties, however, sometimes their methods border on crime.

This month, the big political parties are again leading public discussions about their finances with a series of proposals to find legitimate ways of raising funds. They are in discussions with the government and the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) as the House of Representatives reviews the regulations under the 2011 Law on Political Parties.

The Gerindra Party, which came in third in the 2024 elections, wants the annual state contribution to political parties increased tenfold. Under the current law, political parties get Rp 1,000 (6.25 US cents) for every vote they won from the last national election. The rate goes up to Rp 1,200 and Rp 1,500 for each vote in provincial and regency/city elections, respectively.

Based on its 2024 votes, Gerindra reported this month that it received Rp 20.76 billion this year, up from Rp 18.2 billion in 2024 to reflect the gain in its votes. The party said this money only covers political education programs. To remain financially viable, the ideal sum from the state should be increased to Rp 10,000 per vote, it said, adding that in Germany, political parties received the equivalent of Rp 12,825 per vote.

Gerindra was founded and is chaired by Prabowo Subianto, who won the presidential election last year, and is now leading the coalition government comprising seven of the eight political parties in the House. Gerindra’s demand for more money puts it at odds with the government, which has other big spending priorities in mind.

The Justice Welfare Party (PKS), the leading Islamist party, proposes that political parties be allowed to run businesses to raise funds, an idea that is also being looked at by the Ministry of Home Affairs.

Getting more money in legitimate ways addresses the endemic corruption in political parties. Those against the idea, however, feel that parties need to address the question of their public accountability before they deserve any more funding.

Under the current law, political parties may raise fund three ways: Membership fees, individual or corporate donation and the annual contribution from the state based on the results of the last elections.

Membership fees are likely to be small and probably not fully enforced as parties struggle to enlist new members. Corporations and individuals are usually more interested in donating to the parties’ election coffers. State contributions are also too small for most parties.

Almost all political parties are known to raise and spend money far beyond what they report to the government and which is audited by the State Audit Agency (BPK). Some are bankrolled by their corporate owners, including the NasDem Party, which is owned by media mogul Surya Paloh. The United Indonesia Party (Perindo) is owned by businessman Hary Tanoesoedibyo, while Golkar is nicknamed the pro-business party because it is backed by several wealthy business owners who take turns as its chair.

Many legislators at the national and local level are also required to donate their monthly salaries to the party coffers, and they survive on the extra benefits and opportunities that come with their job, including fees, legitimate or otherwise, in approving bills and projects.

The pressure usually falls on party chairs to raise money to keep the party running. Over the years, several have been sent to jail for corruption, including Romahurmuzy and Surya Dharma Ali of the United Development Party (PPP), Lutfhi Hasan Ishaaq of the Justice Welfare Party, Setya Novanto of Golkar and Anas Urbaningrum of the Democratic Party. Other top-ranking party officials have also gone to jail for corruption, including cabinet ministers who owed their seats to the parties that are members of coalition governments.

However, the buck stops with these chairs or the individuals in the party, in spite of public demands that the court follow the money trail. Should the court do that and find that money from corruption has found its way into party coffers, the court can dissolve and outlaw the party. That, however, would be unprecedented.

What we've heard

The Ministry of Home Affairs’ proposal to create political party-owned enterprises is supported by the ruling coalition. A government official said the government wants political parties to be financially healthy. “Democracy can progress if parties are financially independent,” said the official.